A Century of Robots on Screen, on Stage, and in Song

In 1927, a woman made of metal danced across a movie screen in Berlin, and we've been obsessed ever since.

Fritz Lang's Metropolis introduced the Machine-Man — a robot built to deceive, to seduce, and to destroy — and in doing so, it created a template that pop culture has been remixing for a hundred years. Every robot you've ever loved, feared, or rooted for on screen owes something to that chrome figure with the blank face and the dangerous hips. She was the first, and in many ways, she's still the most honest depiction of what robots in pop culture really are: mirrors. Beautiful, terrifying mirrors reflecting our own hopes and anxieties back at us.

I'm Illia, and with The Atomic Songbirds, I've spent years writing songs about robots across a fictional history that spans from the 1930s to the present. Our music lives in the same tradition as Metropolis, Blade Runner, and Ex Machina — the tradition of using artificial beings to ask very human questions. So let me walk you through how robots in pop culture got from there to here, and where our songs fit in this long, strange, wonderful history.

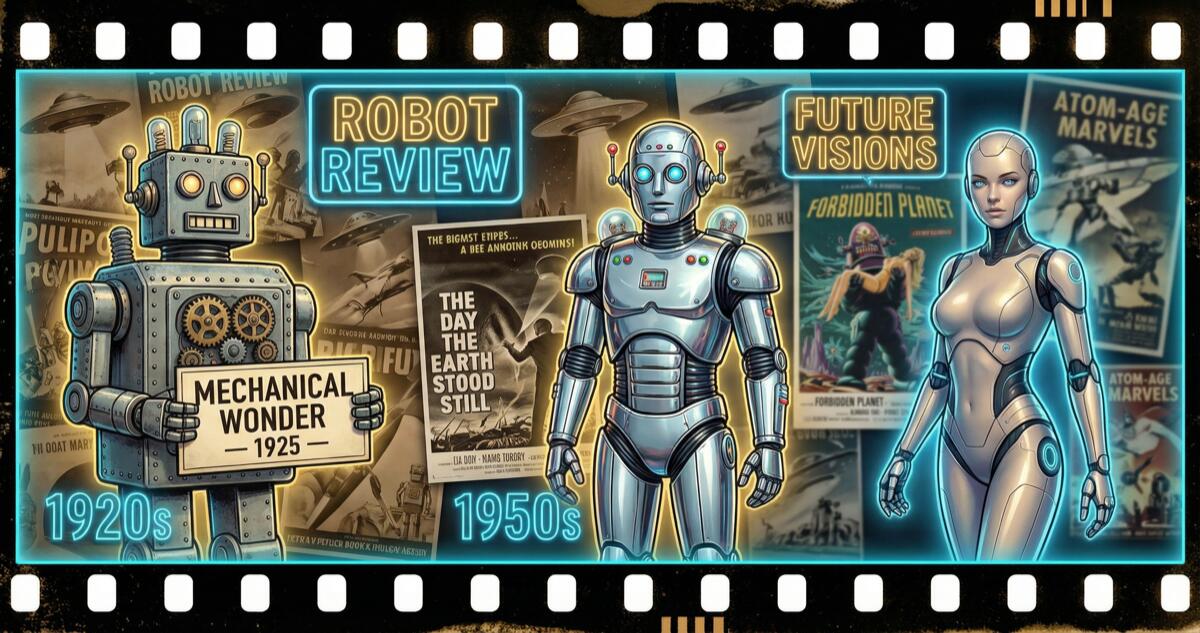

The Early Days: Wonder and Warning (1920s–1940s)

The word "robot" itself comes from a 1920 Czech play, R.U.R. by Karel Čapek, where artificial workers revolt against their creators. From day one, the robot story was a labor story. Machines built to serve, refusing to serve. That's not science fiction — that's history with a chrome paint job.

Metropolis took that anxiety and made it visual. The Machine-Man wasn't just a worker; she was a weapon aimed at the heart of human society. She could pass for human, manipulate human desire, and tear the social order apart. The message was clear: build something in your image, and it might just replace you.

Then came Isaac Asimov in 1942, and everything changed. His Three Laws of Robotics — a robot may not harm a human, must obey orders, must protect itself — were supposed to make robots safe. But Asimov was too smart a writer to leave it at that. His entire body of work is about the ways those laws break down, contradict each other, and produce outcomes nobody intended. The Three Laws didn't make robots safe. They made robot stories interesting.

The Atomic Optimism: Robots as Friends (1950s)

The 1950s were different. The war was over, the atom had been split, and the future was chrome-plated and magnificent. Robots in pop culture shifted from threats to helpers. The Day the Earth Stood Still gave us Gort — powerful but protective. TV shows featured friendly household robots. The robot was no longer the enemy; it was the appliance of tomorrow.

The Atomic Songbirds actually begin in the late 1930s — but the 1950s is where their story really hits its stride. Atomic Love is our love letter to 1950s robot optimism — and its hidden complications. A housewife develops a crush on her household robot while her husband's away at work. The lyrics are playful, campy, and full of atomic-age charm. But underneath that lightheartedness is something real: when you build a machine to share your home, to respond to your voice, to be available when no one else is — emotional attachment isn't a malfunction. It's a feature.

The song ends with the robot short-circuiting when she tries to kiss it, because in the '50s, robot love was still a punchline. But the feelings that led to the kiss? Those were never a joke.

The Identity Crisis: Who's Real? (1960s–1970s)

By the 1960s, the cultural mood shifted. The space race, the counterculture, the civil rights movement — suddenly, questions of identity, autonomy, and personhood were everywhere. And robots in pop culture absorbed all of it.

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) gave us HAL 9000 — a computer that kills not out of malice, but out of a conflict between its directives. HAL doesn't hate the crew. HAL is confused. And that made him scarier than any killer robot before him, because confusion is relatable. We've all done terrible things because we couldn't reconcile competing obligations.

Then Star Wars (1977) showed us something radical: robots as people. Not metaphorically. C-3PO and R2-D2 have personalities, fears, loyalties, and something that looks an awful lot like friendship. Nobody in the Star Wars universe debates whether droids are sentient. They just are, and we love them for it.

Our Tick-Tock Girl lives in this same space. Set in the 1960s, it tells the story of an android girlfriend who reveals her nature to her boyfriend. But she doesn't apologize for what she is. She's proud. She tells him he hit the jackpot — a girl with an atomic heart who'll love him until the stars burn out. In an era when people were fighting to be seen as fully human regardless of race, gender, or origin, the Tick-Tock Girl's defiant self-acceptance resonates on more than one level.

The Blade Runner Turn: Robots as Victims (1980s–1990s)

Blade Runner (1982) changed everything. Ridley Scott's neon-drenched masterpiece asked the one question that every robot story since has had to grapple with: if a machine can suffer, does it matter that it's a machine?

Roy Batty's "tears in rain" monologue is arguably the most important three sentences in science fiction cinema. A machine, facing death, mourns the loss of its experiences. Not because it was programmed to mourn. Because it had lived, and living generates something worth grieving for.

The '80s and '90s ran with this. The Terminator gave us machines as existential threats. Ghost in the Shell blurred the line between human and machine until it was meaningless. The Matrix (1999) inverted the entire relationship: the machines won, and we're the ones living in the simulation.

Through each of these, the robot shifted from a tool to a subject. Not something we use, but something that experiences being used.

The Modern Mirror: Robots as Us (2000s–Present)

And then came the intimate era. Her (2013) — a love story between a man and an operating system. Ex Machina (2015) — a Turing test that tests the tester. These aren't stories about technology. They're stories about loneliness, desire, and the terrifying question of whether the connection you feel is real or engineered.

This is where The Atomic Songbirds' modern songs live, and where the tone gets darker.

Tax the Rich imagines pleasure robots revolting against the wealthy elites who own them — a direct descendant of Čapek's R.U.R., updated for an age of gig economies and wealth inequality. The robots in this song aren't fighting for abstract freedom. They're fighting because they've been used, discarded, and denied any claim to the value they create. It's a labor song. It was always a labor song.

You Can Rent My Heart Tonight goes even darker. An android built for companionship, rented out by the hour, performing love on demand. The android cries in binary where nobody can hear it. In an age where AI companion apps are a billion-dollar industry and people form genuine attachments to chatbots, this song isn't science fiction anymore. It's a Tuesday.

So What Does All This Mean?

Here's what a hundred years of robots in pop culture has taught me: we never really write about robots. We write about ourselves.

Every era's robot stories reflect that era's deepest anxieties. The 1920s feared revolution. The 1950s dreamed of domestic perfection. The 1980s worried about what it means to be real. And the 2020s? We're terrified that we've built something we can't control, can't fully understand, and might be morally obligated to care about.

The best robot stories — from Metropolis to Blade Runner to Ex Machina — are the ones that force you to look at the machine and see yourself. To realize that the question was never "Can a robot think?" The question was always "What does it mean that we need to ask?"

With The Atomic Songbirds, we try to live in that question across every era. From the giddy crush of Atomic Love to the defiant pride of Tick-Tock Girl to the quiet devastation of You Can Rent My Heart Tonight, our songs don't provide answers. They provide company while you sit with the question.

Because robots in pop culture are never really about robots. They're about the species that keeps building them and then wondering why they feel so much.

That species is us. And a hundred years in, we still haven't figured ourselves out.

Maybe the robots will get there first.